Frieze London 2022

Stand E3

12 - 16 October 2022

Head-Image

For Frieze London 2022, Goodman Gallery presents works by

RUBY ONYINYECHI AMANZE ∙ GHADA AMER ∙ EL ANATSUI ∙ KUDZANAI CHIURAI ∙ LEONARDO DREW ∙ CARLOS GARAICOA ∙ DAVID GOLDBLATT ∙ DOR GUEZ ∙ NICHOLAS HLOBO ∙ ALFREDO JAAR ∙ SAMSON KAMBALU ∙ WILLIAM KENTRIDGE ∙ GRADA KILOMBA ∙ CASSI NAMODA ∙ SHIRIN NESHAT ∙ SAM NHLENGETHWA ∙ RAVELLE PILLAY ∙ ZINEB SEDIRA ∙ YINKA SHONIBARE CBE RA ∙ SUE WILLIAMSON

ruby onyinyechi amanze

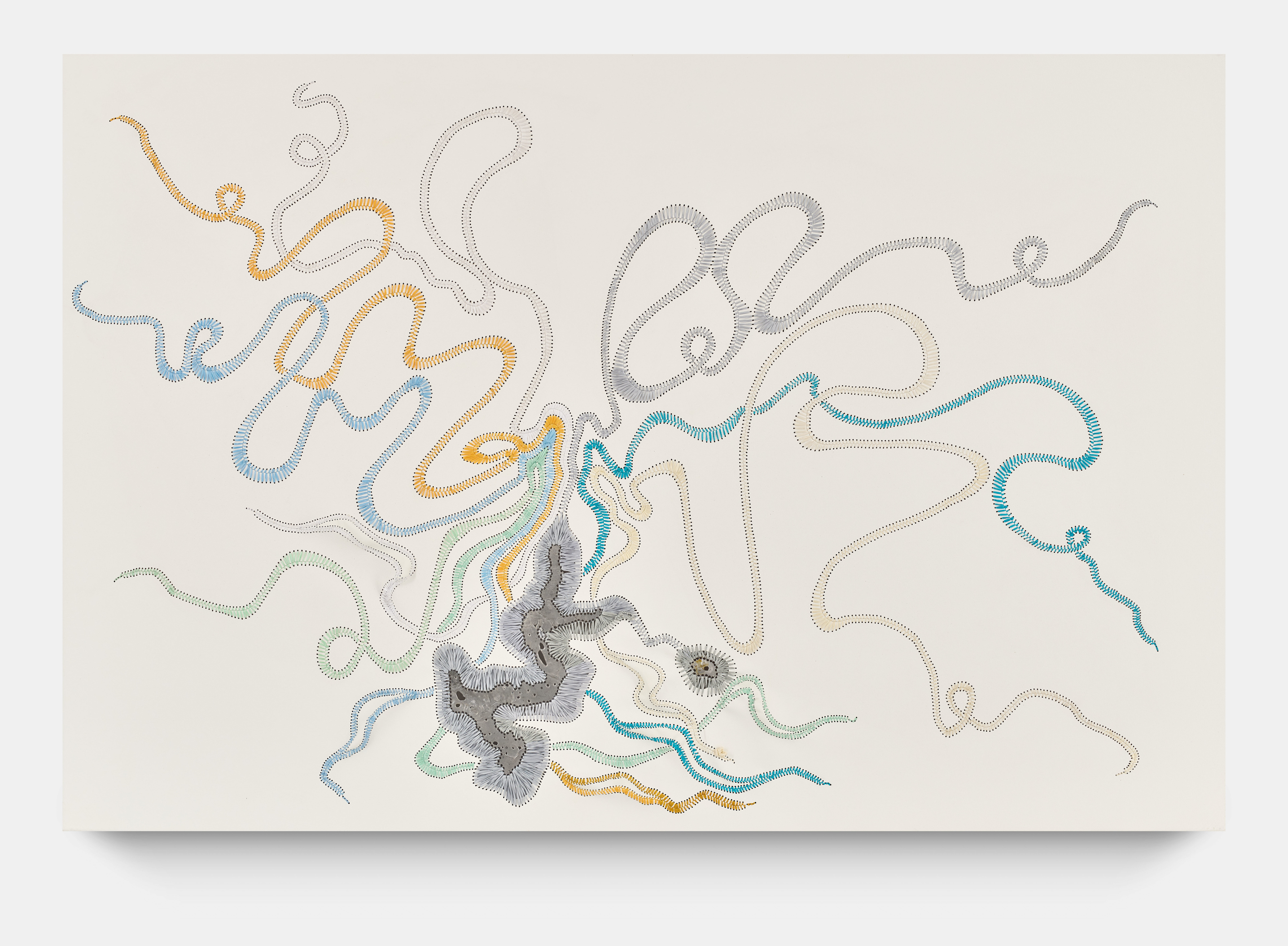

to dive upwards or SWIMMING POOL + ADA, 2022

Graphite, ink, photo transfers, pencil crayons, acrylics on paper

180.3 x 146 cm / 71 x 57.5 in.

Using a palette of seven recurring visual elements, amanze creates an expansive world that pushes against the idea of narrative. With no hierarchy, the seven include: architecture, birds, ada, bike, swimming pool and audre, with the final element being the paper itself. For this series, positioned as a choreographer of sorts, amanze experiments with placing these elements into pairings. amanze’s practice pulls inspiration from the spatial negotiations found in design and the three-dimensional practices of dance and architecture.

As part of an ongoing exploration, the malleability of space remains the primary antagonist. A nameless, chimeric universe is simultaneously positioned between nowhere and everywhere. Each “duet” of two elements is suspended in an infinite space with no gravitational axis as part of the artist’s attempt to push the boundaries of depth and scale. Incorporating materials from graphite, to ink, to photo transfers, amanze slices and cuts imagery to create spaces and shapes where the elements meet.

Why pairings? “In my studio practice, I frequently and arbitrarily create restrictions for myself to work with. It is a numbers game, a puzzle of sorts, making drawings through a process of parts to a whole or a whole into parts” - amanze. In earlier work, the sudo-human figures of ada and audre featured as main characters. This series explores what it means to place the two selected elements on a level playing field and to reject a hierarchy between them.

Ghada Amer

Witches, 2022

Acrylic, embroidery and gel medium on canvas

127 x 152.4 cm / 50 x 60 in.

The citations that are carefully embroidered on Amer’s paintings do not speak directly about the status of women in a particular society nor do they address what is going on in the US or in the Middle East. Rather, her paintings remind the viewer that women must be vigilant over the rights they have acquired and never take their liberation for granted: “In Western societies, there is an assumption, especially among the younger generations, that the battle of the sexes has been won, that women have been liberated, and that their rights are secure. And yet, we are witnessing today a sharp regression of women’s rights and a stark rise of violence against women. However, in countries where one assumes women’s rights to be limited or absent, such as in Egypt, Iran, Afghanistan, or Mexico, women of the younger generation know they have a lot to gain from fighting for those very same rights that are eroding in the West. So they are not letting down their guard and they are continuing to fight fiercely.” “we were taught to fear the witches and not those who burned them alive” - Unknown

El Anatsui

Sovereignty, 2021

Aluminium, copper wire and nylon string

360 x 315 cm / 141.7 x 124 in.

Jointly presented by Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and October Gallery, London

El Anatsui is one of the most significant living contemporary artists. Anatsui is respected for his contributions to African modernism. Within his practice, he explores geometry and form through materiality. A key contributor to the Nsukka art school and various artistic movements that ensued in West Africa, Anatsui has found interesting ways to negotiate the complexities of what it means to create as an artist from the continent. Sovereignty uses a combination of biotic, non-linear and ordered lines chaotically tangled to reflect the violently established laws that organise the flow of humans through restrictions, while also drawing attention to natural pathways and channels.

Kudzanai Chiurai

We Live in Silence I, 2017

Pigment ink on fibre paper

Work: 150 x 193.5 cm / 59 x 76.2 in.

Edition of 10

We Live in Silence, forms the third and final installment in a three-part series that began with Revelations (2011) and continued with Genesis [Je n’isi isi] (2016). Taken as a whole, this ambitious body of work disrupts what the artist refers to as ‘colonial futures’, creating ‘counter-memories’ within his images to contest dominant colonial narratives.

Taking Mauritian filmmaker Med Hondo’s critically-acclaimed 1967 drama Soleil Ô as its starting point, responding, in particular, to the colonial mindset that forms as a result of white-washing and cultural erasure, the film responds to the colonial mindset that African migrants to Europe are to think, speak and understand language like their colonisers. Chiurai dissects the film through similitude, recreating scenes intercut with visual references from popular culture, religion and art historical sources to stage alternative colonial histories and futures.

The single-channel film from which this photographic essays derives also re-positioned the female role in recent struggle histories - recasting the lead character as a woman in the black liberation narrative to challenge the gender-bias inherent to such narratives.

Leonardo Drew

Number 265, 2020

Wood and paint

80 x 64.8 x 31.8 cm / 31.5 x 25.5 x 12.5

Drew is known for creating wall-based abstract sculptural works that play on a tension between order and chaos. The artist typically uses manipulated organic materials to create richly detailed works – seemingly bursting from the walls – which resemble densely populated cities or urban wastelands and evoke the mutability of the natural world.

Materials include wood, cardboard, paint, paper, plastic, rope, string and tree trunks. The artist subjects these elements to processes of oxidation, burning and weathering. These labour-intense manipulations mimic natural processes and transform these objects into sculptures that address formal and social concerns as well as the cyclical nature of existence. Drew’s long-standing interest in lifecycles and how human labour leaves traces of life behind is an important aspect of the materiality of the work.

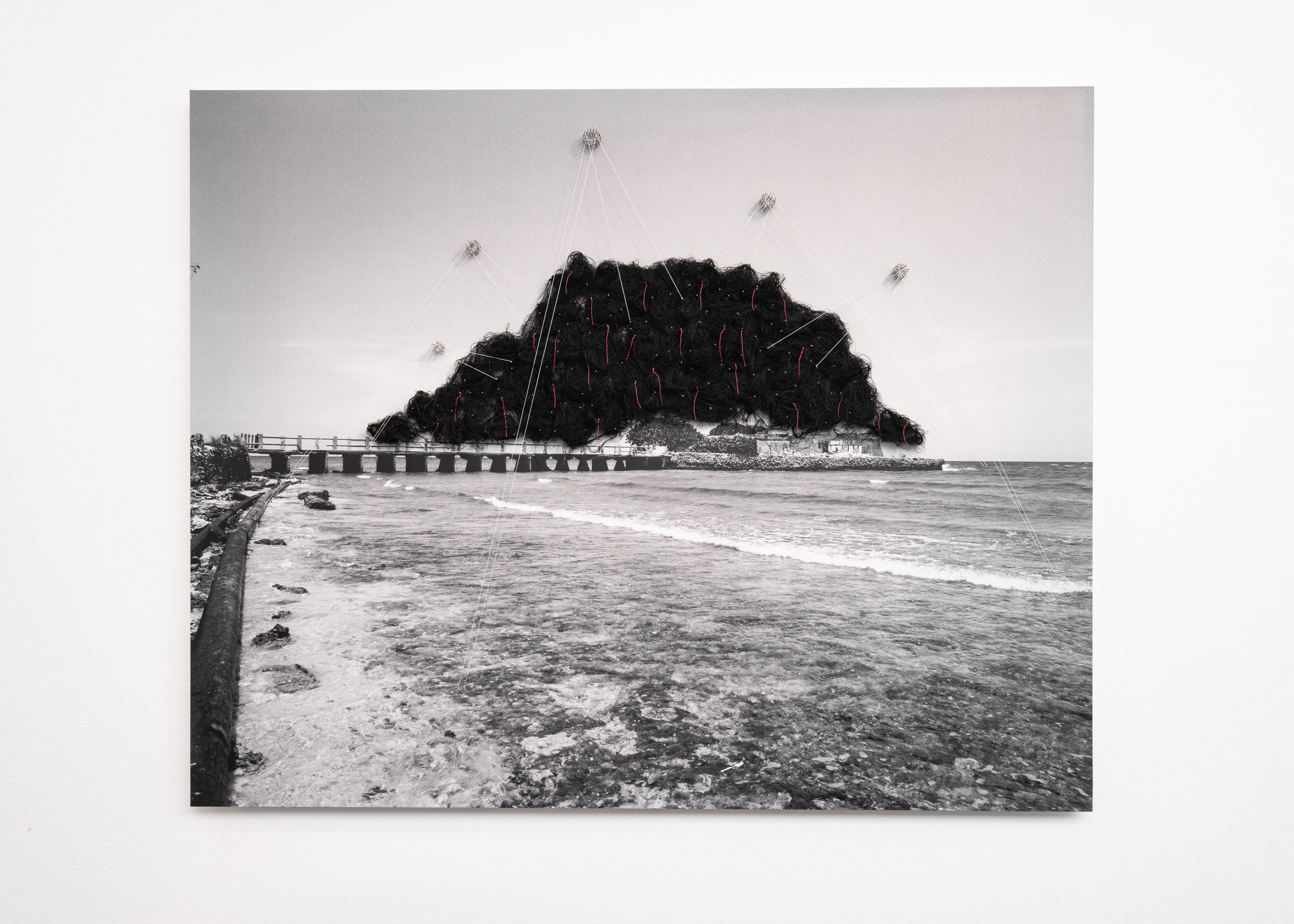

Carlos Garaicoa

Sin titulo (Cayuelo) / Untitled (Cayuelo), 2018

Pins and threads on lambda photograph mounted and laminated in black Gator Board

125 x 160 cm / 49.2 x 63 in.

For various years, Garaicoa has been working on a series of black and white mural photographs of different buildings in Havana integrated with thread drawings. In a new turn of this series we find the work Untitled (Cayuelo) (2018) where he moves the eye to the relation of the trees and garden with the city, making an statement about the tension between urbanism and nature. This develops the interest that the artist has had for years in gardens and non-natural processes inside the city.

David Goldblatt

Cafe-de-Move-On, Braamfontein, Johannesburg

Silver gelatin hand print

Image: 34.5 x 23.1 cm / 13.6 x 9.1 in.

Renowned for a lifetime of photography exploring his home country, Goldblatt produced an unparalleled body of work within the city of Johannesburg, where he lived for 50 years. At age 17, Goldblatt would hitchhike from Randfontein, the small mining town where he was born, into Johannesburg. He walked around the city until the next morning, talking to night watchmen and following his intuition: “People would ask me what I was doing, and I would say, ‘I’m poeging. I’m walking around the city; I’m learning the city, and trying to take photographs.” i This process became the foundation of his practice.

“Johannesburg”, he wrote, “is not an easy city to love. From its beginnings as a mining camp in 1886, whites did not want brown and black people living among or near them and over the years pushed them further and further from the city and its white suburbs. Like the city itself my thoughts and feelings about Joburg are fragmented. I can’t easily bring a vision or a coherent bundle of ideas to mind and say, ‘That’s Joburg for me.’ Over the years I have photographed a wide range of subjects, each was almost self-contained, a fragment of a whole that I’ve never quite grasped.”

David Goldblatt

‘Location in the sky’: the servants’ quarters of Essanby house. Jeppe Street, Johannesburg, April 1984

Silver gelatin hand print

Image : 35 x 28 cm / 13.8 x 11 in.

Location in the sky captures guarded buildings in the centre of Johannesburg where migrant workers lived. The buildings reflect the legacies of segregationist policies of the apartheid government which controlled the flow of Black people in and out of cities. Through this series, Goldblatt captures place as well as the spirit of the people who inhabit the place, he noted; “To me, there is a seamless relationship between people and their places.

People are marked by the places in which they have their being, and there are few places unmarked by the passing, the hand, the presence of people….There is a casual intimacy in this mutual relationship that inevitably permeates much photography. I don’t need people in a photograph to know that people are there.” — David Goldblatt, Photographers References, 2014.

Samira’s story is a starting point for Guez’s artwork and the Christian-Palestinian Archive project (CPA). Guez founded the CPA, 2006 after discovering a suitcase filled with old photographs and documents at his grandparent’s home in Lydda. His family’s photographs were the first pillar of the archive. Today the CPA is an independent entity containing thousands of digital images from Christian-Palestinians across the world. The CPA gathers photographs through open calls.

This work tells the story of Dor Guez’s grandmother, Samira Monayer, and her siblings between 1938 and 1958 through a series of manipulated archival materials the artist calls “scanograms.” Each image documents significant events before the family was expelled from Jaffa, forced to relocate to Lydda, Amman, Cyprus, Cairo, and London. Two of the scanograms depict Samira’s wedding in Lydda’s ghetto, 1949. It was the first Palestinian wedding after the Palestinian exodus from land claimed by Israel (known as al-Nakba, “the catastrophe”).

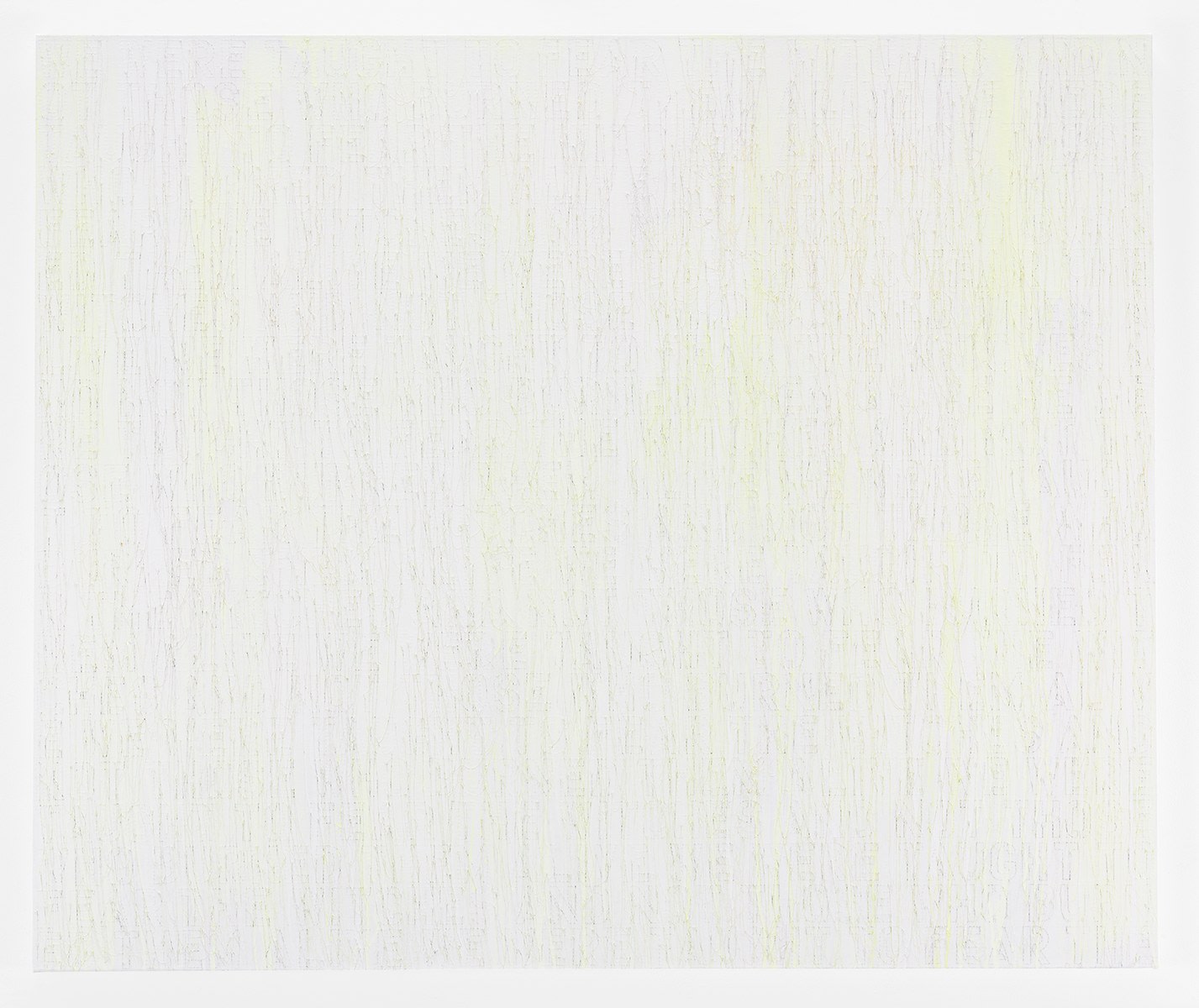

Nicholas Hlobo

Akanamva namphambili, 2021

Ribbons and lead on Belgian Linen

120 x 180 cm / 47.2 x 70.9 in.

Working with various found objects and materials — leather, rubber, bronze, ribbons, copper and brass —Nicholas Hlobo considers his artistic practice to be a kind of autobiography through which he articulates a sense of self. Through an obscured grammar within a language of abstraction, Hlobo explores his psychological, emotional and spiritual journey.

“My work is about my journey, how I relate to myself and to the outside world. I’m very curious about the invisible, intangible and incomprehensible aspects of that journey and there is always a slipperiness to the process of figuring it out”, says Hlobo. Hlobo uses materials that have resonance to his personal memories, he explains; “Materials are found and used as a way to add more layers to the narrative. And how they are intervened with forms part of becoming a language that tells the story. Found objects have their own stories with various patinas depending on where they come from.”

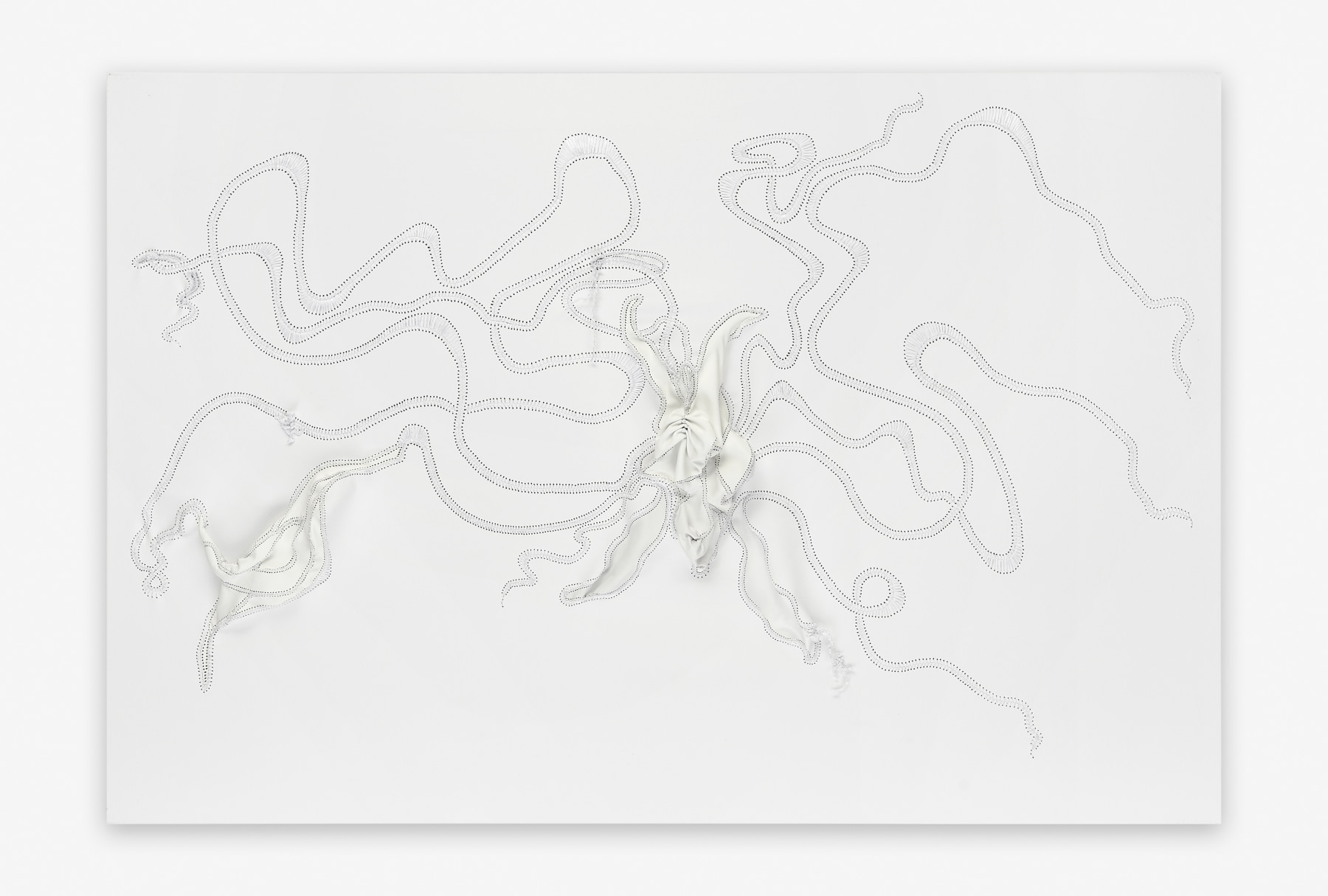

Nicholas Hlobo

Ivulandlela, 2018

Ribbon and leather on canvas

120 x 180 x 20 cm / 47.2 x 70.8 x 7.8 in.

Alfredo Jaar

Other People Think, 2012

Lightbox with black and white transparency

50 x 50 x 10 cm / 19.7 x 19.7 x 3.9 in.

STD 9/10

Edition of 10

Other People Think is a homage by Jaar to John Cage, created in 2012 on the occasion of Cage’s Centennial. Written in 1927, “Other People Think” is one of Cage’s earliest writings, delivered by him at the Hollywood Bowl where, then a student at Los Angeles High School, he won the Southern California Oratorical Contest. Although Cage was only 15 years old at the time, his essay frames a bold critique and portentous analysis of North and South American relations and continues to have incredible resonance and relevance to contemporary culture and politics. As a Chilean artist living in the United States 85 years later, Jaar still works with the imbalances of this historically stagnant relationship. Reintroducing this acute text to today’s audience, Jaar hopes to bring Cage’s teachings back to light.

Samson Kambulu

Antelope, 2021

Bronze

100 x 49 x 24.5 cm / 39.4 x 19.3 x 9.6 in.

Edition of 3

Antelope recreates a 1914 photograph discovered by Samson Kambalu of Baptist preacher and pan-Africanist John Chilembwe and European missionary John Chorley. Chilembwe led an uprising in 1915 against British colonial rule in then Nyasaland, now Malawi triggered by the mistreatment of refugees from Mozambique and the conscription to fight German troops during WWI. He was killed shortly after, and his church destroyed by the colonial police.

Antelope depicts Chilembwe at almost twice the size of Chorley, elevating his story to realign history and bring to the fore an untold and underrepresented narrative of resistance against colonial rule. The hat Chilembwe wears marks an act of defiance against colonial rule, as it was forbidden for Africans to wear hats in front of white people. The title of the work also references Chilembwe’s hat, placed high on the preacher’s head creating two peaks, like antelope horns. A large scale version was commisioned for Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth in London and was unveiled in September 2022.

Samson Kambalu

Antelope, 2021

PLA 3-D printed Ghost

100 x 49 x 24.5 cm / 39.4 x 19.3 x 9.6 in.

Edition of 3

William Kentridge

Cursive, 2020

Bronze set of 40 sculptures

Shelf: 133.5 x 190 x 26.5 cm / 52.6 x 75 x 10.4 in.

Variable dimensions of sculptures

AP 1/3

Enquire

Cursive is the third in a series of William Kentridge’s Lexicon bronzes — an accumulation of elemental symbols within his broader practice. This series of bronze sculptures functions as a form of visual dictionary. The sculptures are symbols and ‘glyphs’, a repertoire of everyday objects or suggested words and icons, many of which have been used repeatedly across previous projects. The glyphs can be arranged to construct sculptural sentences and rearranged to deny meaning. “The glyphs started as a collection of ink drawings and paper cut-outs, each on a single page from a dictionary.

Previously I had taken a drawing or silhouette and given it just enough body to stand on its own feet - paper, added to cardboard and put on a stand. With the glyphs, I wanted a silhouette with the weight that the shape suggested. A shape not just balancing in space, but filling space. Something to hold in your hand, with both shape and heft.”

William Kentridge

Flowers for Suzanne, 2018

Handwoven Mohair Tapestry Work

(approx): 200 x 150 cm / 78.7 x 59 in.

STD 3/6

Marguerite Stephens and Kentridge have been working together on tapestries for the past twenty-four years. The longstanding collaboration between the two studios creates expressive artworks in which Stephens translates the artist’s collage drawings for the very different materials and techniques of tapestry-making.There is a contemporary sensibility in the transformation of a Kentridge image into a series of pixilated decisions: the 2000 threads of the warp, the many thousands of thread of the weft. The coherent final image is the result of many specific decisions.

A tapestry also relates in scale to a mural. But these are removable murals, and in this way relate to projections too. So the artist thinks of these sometimes as fixing the frames of a projection in the taut strings of the weaving. In translating the artist’s drawings and collages into tapestries, there is a process of amplification, expansion and refinement. They are redrawn and further detailed in thread. Lines of red, muted in the collages and drawings, become brighter. New lines are added too, giving the work a greater sense of flux, as if Kentridge was rethinking and reimagining the scene.

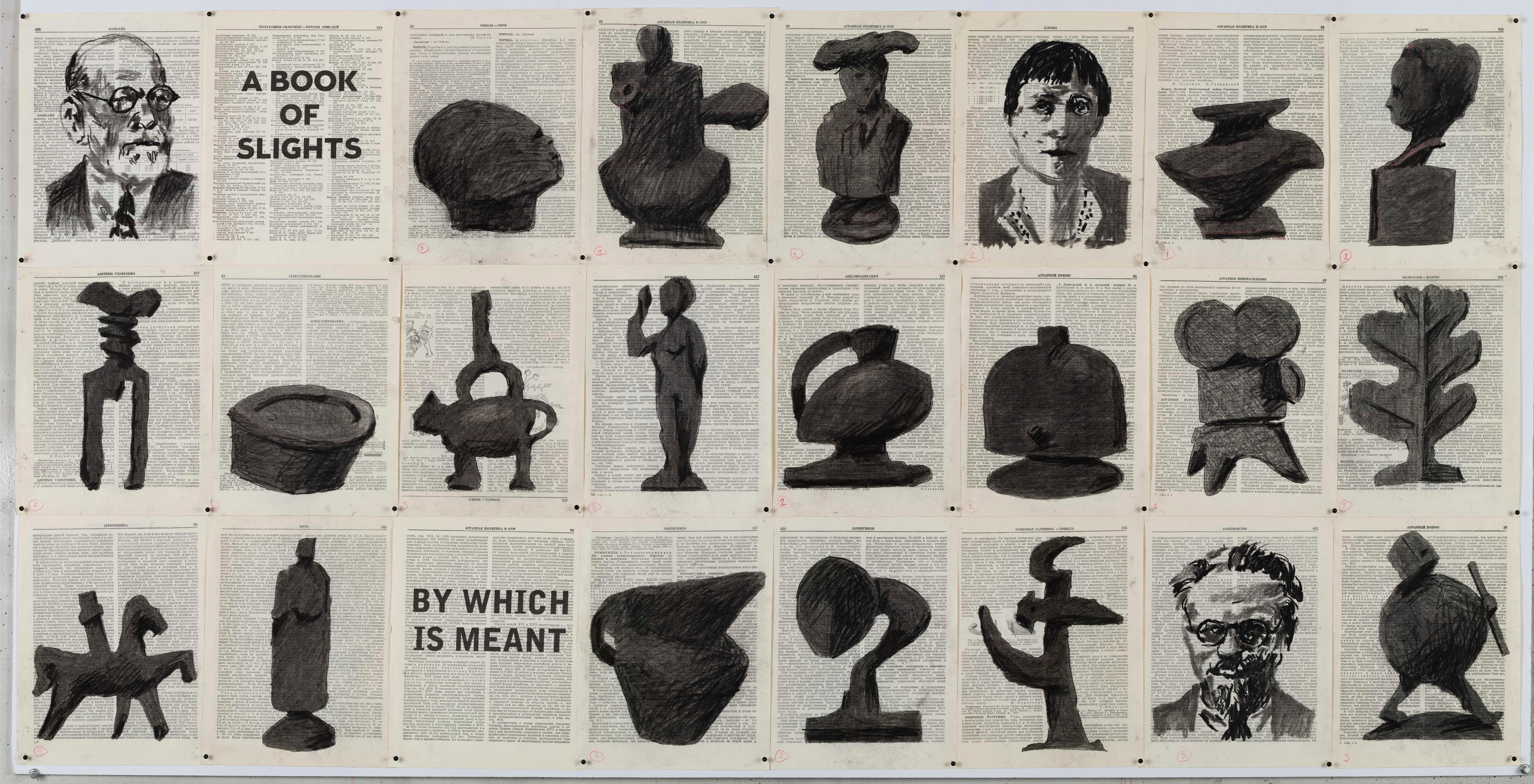

William Kentridge

Book of Slights, 2017

Charcoal on found encyclopedia pages

Work: 67 x 152 cm / 26.4 x 60 in.

Frame: 88.5 x 163.5 x 5 cm / 34.8 x 64.4 x 2 in.

William Kentridge’s Book of Slights was drawn in conjunction with the making of Kentridge’s flip book film, Soft Dictionary. Flip book films are characterised by drawings in ink and charcoal and text, which dance across the pages of found books. Brought to life once opened by the artist’s hand, the pages of these books turn by themselves, presenting fragmented anti-narratives of text and images.

Soft Dictionary is a visual record of a series of thoughts emerging and disappearing – lists of drawings made and never made, historical figures, personal references. The film tries to document fragments of the non-sequiturs lodged in our heads, all of which are props in our efforts to understand the world: the very randomness of thoughts providing some of the richness of understanding. In its attempt to follow multiple streams of consciousness, it travels the boundary between incoherence, in the arbitrariness of images and references; and our constant need to make connections between images and references.

O Barco/The Boat is an installation, composed of 140 blocks which form the silhouette of the bottom of a ship and carefully draw the space created to accommodate the bodies of millions of Africans, enslaved by European empires. In the Western imaginary, a boat is easily associated with glory, freedom and maritime expansion, described as “discoveries” but, in the artist’s view, “a continent with millions of people cannot be discovered” nor “one of the longest and most horrendous chapters of humanity – Slavery – can be erased”.

18 of the blocks at the center of the installation are engraved in gold text with a poem written by the artist. From this the individual Untitled Poems are extracted This first large-scale installation by Grada Kilomba, which in its first iteration stretched 32 meters along the Tagus river, invites the audience to enter a garden of memory, in which poems rest on burnt wooden blocks, recalling forgotten stories and identities. It is currently staged at Somerset House, London. What stories are told? Where are they told? How are they told? And told by whom? These are questions that arise when entering this installation.

Cassi Namoda

Bar Texas 1973, 2022

Oil on linen

Work: 51 x 61 x 3 cm / 20 x 24 x 1.2 in.

Frame: 64 x 79 x 7 cm / 25.2 x 31.1 x 2.8 in.

By referencing Mozambican photographer Ricardo Rangel reflections on life in Mozambique found in his ‘The Texas Bar’ series, Namoda marks moments of celebration and highlights the historic residue on Black women’s lives, offering new readings that interrogate the context that informed the original images. Namoda uses distinct visual strategies to push against exoticising readings of her work: recurring figures possess piercing green eyes which state definitely back at the viewer and the flat colour backgrounds remove context and sense of place.

The artist applies elements of photorealism to parts of the body to insert layers and reinforce surrealist sentiments. For example, the skin of the figures is illuminated, presenting an essence of light entry but without indication of its source. The impression of self-illumined figures suggests a divine otherworldly presence.

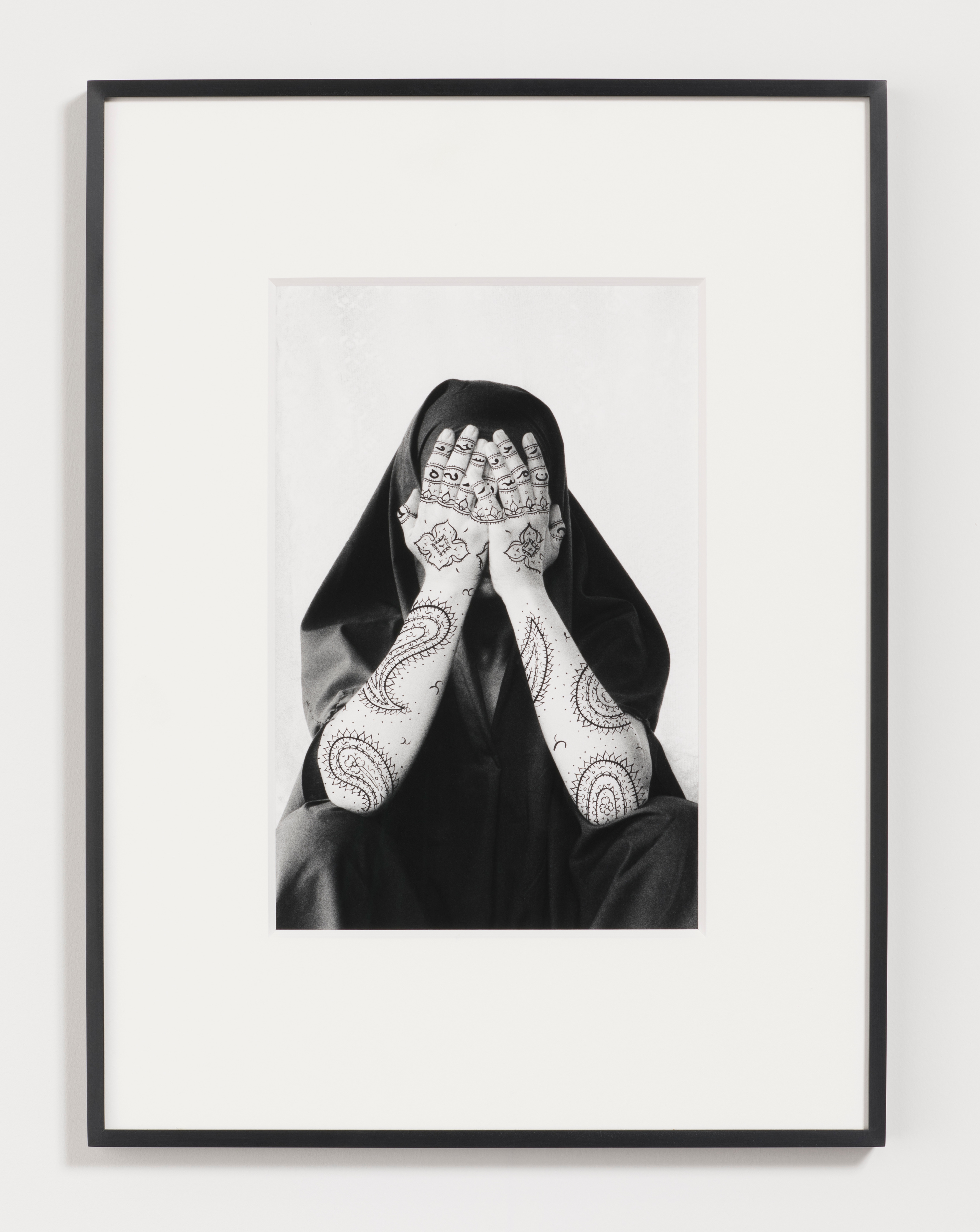

Shirin Neshat

Stripped, 1995

Black and white RC print and ink (photo taken by Kyong Park)

Work: 35.6 x 27.9 cm / 14 x 11 in.

Frame: 53.3 x 40.6 cm / 21 x 16 in.

Edition 9 of 10

Shirin Neshat’s work explores issues such as gender politics, self definition and religious authority. Primarily using female imagery, she examines political and societal change in Iran. For the artist, Iranian women embody this political transformation, so that “by studying a woman, you can read the structure and the ideology of the country”. Neshat occupies an influential and highly respected position in the international contemporary art world, not only for her formidable artistic talent but also for her long history as a writer and cultural worker.

Her socially-based practice uncovers hidden histories and engages with marginalised lived experiences; constructing expanding visual archives which claim legitimate, visible spaces for her subjects. By proposing these different modes and perspectives of representation, Neshat’s works serve as prime examples of the nexus of art and social activism.

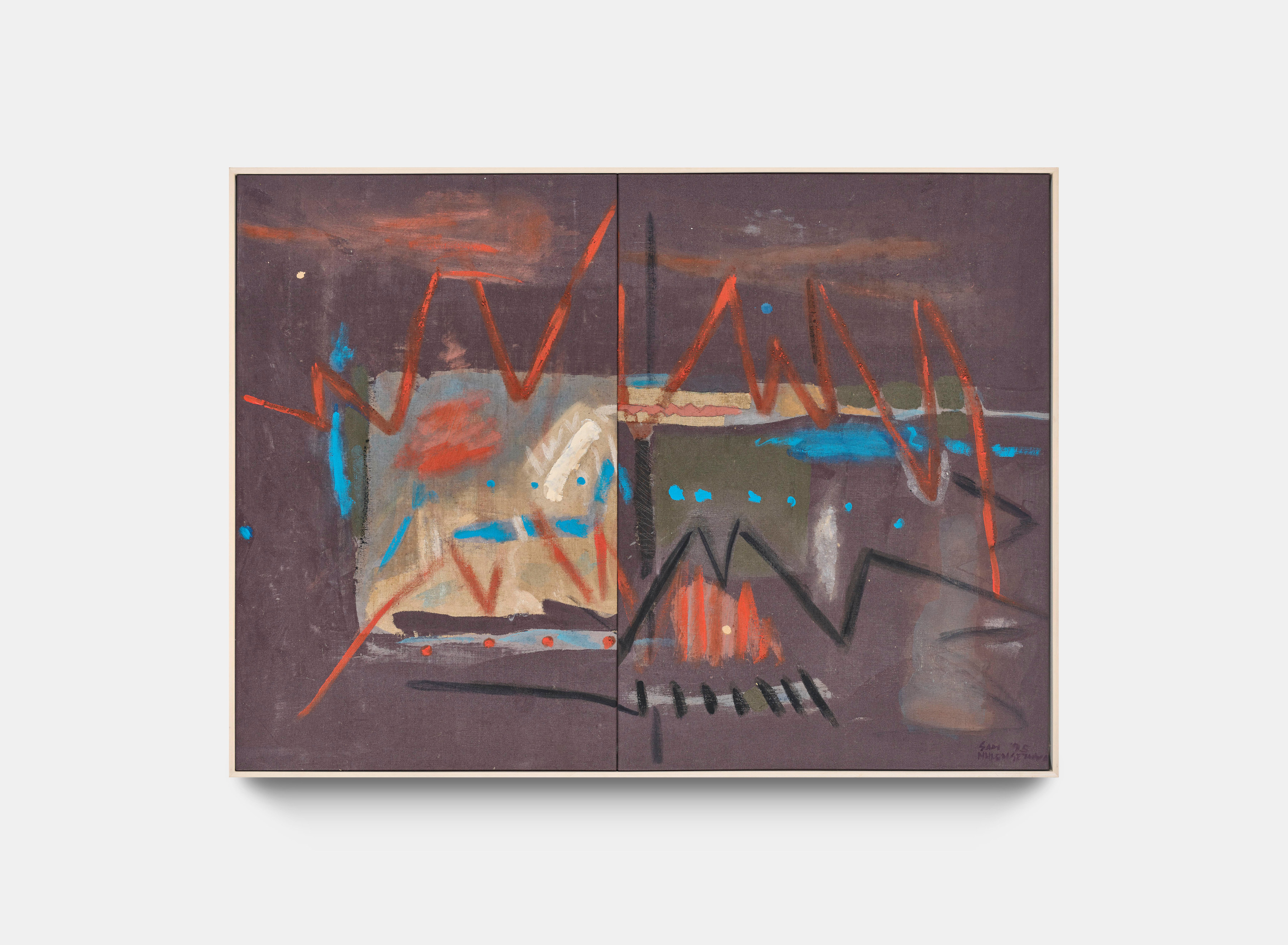

Senegal III forms part of a series of abstract works created by Sam Nhlengethwa during the Africa 95 workshop held in Dakar, Senegal. The workshop, sponsored by the British Council, was attended by artists from South Africa, including David Koloane, the rest of the continent and Britain. Nhlengethwa has been working in abstract forms since 1985. This particular work was inspired by Nhlengethwa’s interaction with the local colour palette in Senegal, which he calls “natural, earthy colours”. This work is his interpretation of that impression.

Ravelle Pillay

night swim, 2022

Oil on canvas

130 x 180 cm / 51.2 x 70.9 in.

As a descendant of labourers who were transported to the former British colony of Natal as part of a larger system of Indian indenture, Pillay’s work is closely informed by legacies of colonialism, and their reverberations in the present. Pillay uses painting and drawing as a material means through which to explore how colonial legacies have found form in personal and collective memory, the natural world, and in the idea of haunting.

Pillay’s borrowed archive of her grandmother’s photo albums provides a foundation to the subject matter of her paintings and into understanding her family’s history within a larger narrative: the displacement of indentured migrants, the still-present spectres of Apartheid, and of place and belonging. As Pillay writes, “I started to think more about life-making inside of these systems, how lives were made ‘in spite of’ and ‘in defiance’.”

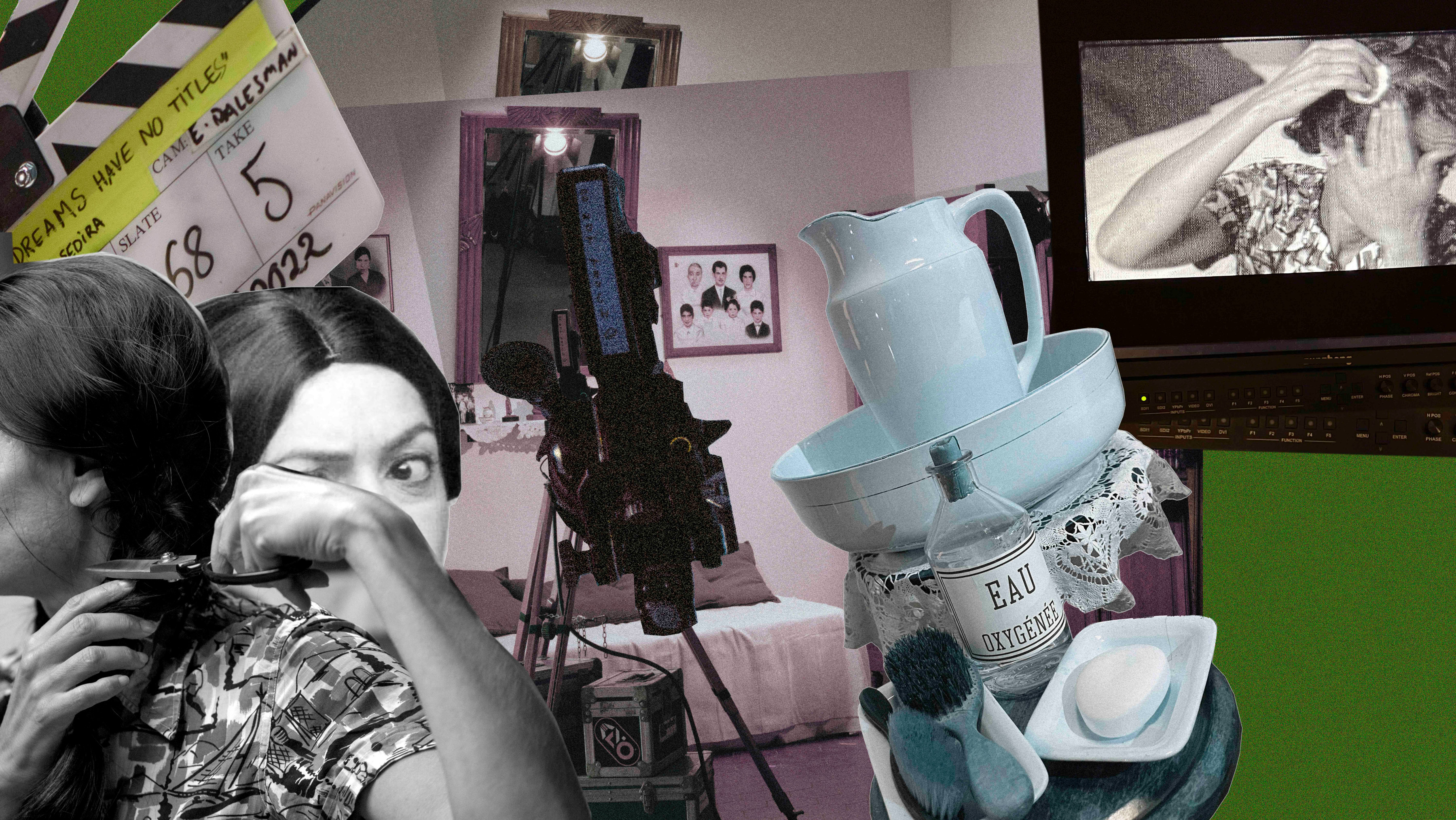

Dreams Have No Titles [The Battle of Algiers], 2022

Collage from analogue photographs

90 x 120 cm / 35.4 x 47.2 in.

Edition 1 of 3

Over the fifteen years of her practice, Sedira has enriched the debate around the concepts of modernism, modernity and its manifestations in an inclusive way. She has also raised awareness of artistic expression and the contemporary experience in North Africa. She found inspiration initially in researching her identity as a woman with a singular personal geography. From these autobiographical concerns she gradually shifted her interest to more universal ideas of mobility, memory and transmission. Full of her fascination for the relationship between mother and daughter, her vidéo Mother Tongue (2002), depicts three generations of women and raises the issue of transmission in a globalized world. Sedira has also addressed environmental and geographical issues, negotiating between both past and future. Using portraits, landscapes, language and archival research, she has developed a polyphonic vocabulary, spanning fiction, documentary and more poetic and lyrical approaches. Sedira has worked in installation, photography, film, video and she has recently returned to object-making. Preserving and transmitting memories of the past in order to leave a legacy for the future has often been at the core of Sedira’s work.

Zineb Sedira

Dreams Have No Titles [Le Bal], 2022

Collage from analogue photographs

90 x 120 cm / 35.4 x 47.2 in.

Edition 1 of 3

Way of Life (maquette), 2020

Wood, paper and photograph model

67 x 90 x 49 cm / 26.4 x 35.4 x 19.3 in

Edition 3 of 3, with 2AP

Yinka Shonibare CBE RA

Fabric Bronze (Red, Yellow, Blue), 2022

Bronze sculpture, hand-painted with Dutch wax pattern.

95.5 x 106.5 x 78 cm / 37.6 x 42 x 30.7 in.

Fabric Bronze is a series of bronze sculptures, each of which is hand-painted with a Dutch wax textile pattern, that explore the notion of harnessing the wind and freezing it in a moment of time. The work manifests as a three-dimensional piece of fabric that appears to be blowing in reaction to the natural elements of the surrounding environment.

The tension of these abstract works will be heightened by the contrast of the media used, and the delicate movement recreated. Here, the piece refers the solidity of a sculptural object, whilst also encapsulating the naturally occurring phenomenon of wind. The structure is deconstructed by patterns normally associated with soft wearable textile.

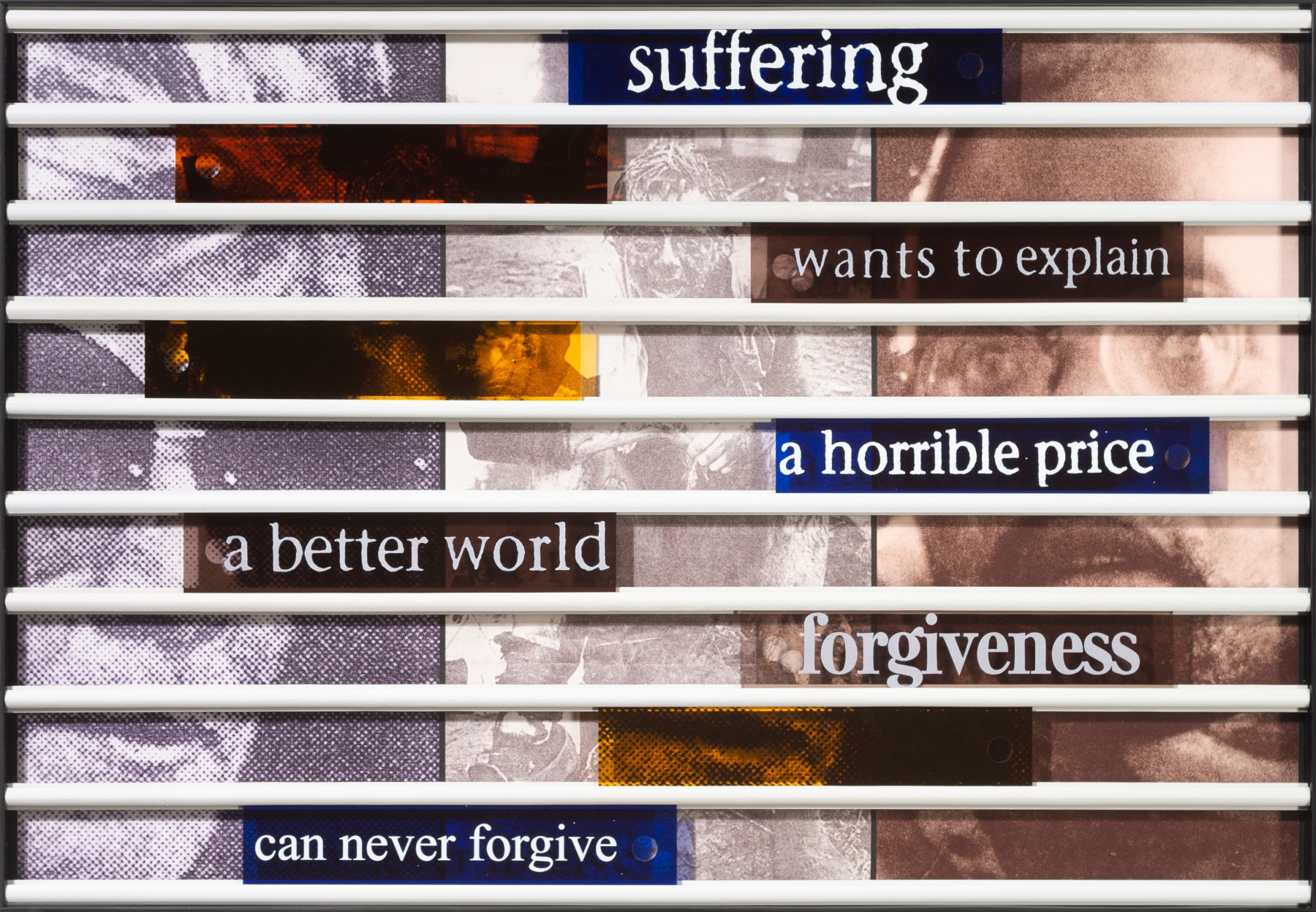

Sue WIlliamson

Truth Games: Mrs Jansen – can never forgive – Afrika Hlapo, 1998

Laminated colour laser print, wood, metal, plastic

84 x 121 x 6 cm / 33 x 47.6 x 2.4 in.

Edition 3 of 3

Truth Games highlights the most important cases investigated by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Each piece pictures an accuser, a defender, and an image of the event in question. Evidence taken from press reports summarises the accusations and defence. These texts are printed on slats obscuring sections of the work. In order to see hidden parts of the images, viewers must slide the slats across the work to uncover what is beneath.

Is the truth finally coming out or is it still hidden? Frederick Jansen was the victim of mob violence in 1980 in the squatter camp of Crossroads, Cape Town, when his small truck was stoned, overturned and set alight. He died the following day. Afrika Hlapo was jailed for his part in the killing. Seeking reconciliation. Hlapo, said his intention had been to seek a better world for South Africa. He received amnesty from the TRC in 1999, and expressed his desire to meet with the Jansen family, a request refused by Jansen’s widow, Pearl.